A reader seeks help understanding why Martin 000 guitars in the lower price ranges are not called OM.

I really enjoy the site. Especially the information about Martin Guitar.

Can you help me better understand why Martin uses the “000″ (triple aught) designation for orchestra bodied models below the 18 Series, when “OM” would be a more accurate designation since they have a standard length scale?

Signed,

Jim in Pennsylvania

Spoon writes:

(Updated July 3, 2019)

Hi Jim,

Thank you for your kind words and interesting question.

I am going to answer your question, and then use it as a springboard to address the whole 000 vs. OM issue.

The simple answer to your actual question is, the 25.4″ string scale, known as the “long scale,” became the industry standard for guitars with that body size, so Martin decided to go with the long scale for the sake of direct competition. And the name of “000” for that size was more well known generically than “OM.”

The “short-scale” neck, measuring 24.9″ and used on smaller Martin body sizes, survived on certain traditional 000 models made in Style 18 and above, and is now making a resurgence, thanks to the recent interest in vintage and retro style guitars.

As to traditional Martin 000s vs OMs, the Martin OM and 000 have the exact same body size in terms of shape and depth. But overall they are not the same thing.

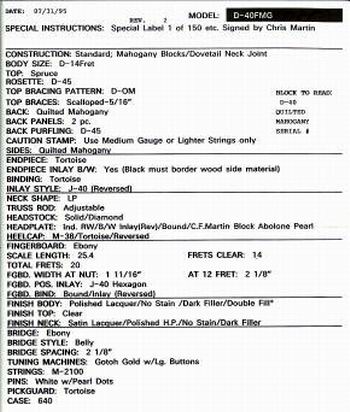

The 000s from the late 1940s on up until modern times were made with a short-scale neck that has the 1-11/16″ width at nut, with non-scalloped 5/16″ bracing.

The OMs, which were sold from 1930 to 1933, and did not appear again in the main Martin line until 1990, have a long-scale neck, which makes them louder and more powerful, and 1/4″ scalloped bracing that makes them more resonant with greater projection than a comparable 000.

This major difference remained the case with all Martin 000s and OMs made in Style 18 and higher until quite recently.

** I must confess, only now as I review this posting in March of 2016 do I realize how clearly the previous paragraphs were composed by an OM player, who prefers that design over the traditional 000s. So I shall balance it as best I can by pointing out that the short-scale 000s certainly have their fans, and for good reasons.

The traditional 000s provide a more-intimate experience by comparison to the OMs. They launch a very clear and defined voice of fundamental notes, while also providing the guitarist with a subtler yet expressively reactive character that very much responds to subtle changes in playing, even if that does not shout out to the room in the same way an OM does. But it still inspires the player, and the results still translate to the broader audience, even if that happens in subtler ways.

And, for some players, the most important differences are found in the shorts-scale’s lower string tension and the fact the frets are laid closer together. The looser strings allow them to be bent farther to achieve higher notes, and the condensed fingerboard allows guitarists to achieve stretches across more frets than they could otherwise make.**

Also, at the time the decision was made to offer the lower-priced Martin 000s in the long scale, there were actual OM models offered in Style 16 and Style 15, as well as the Road Series and 1 Series. OMs typically differed from 000s in various ways other than scale length, even though they shared the same dimensions in terms of body size. The OM had lighter bracing and wider string spacing than the 000, which made them popular with fingerstylists and players with larger than average hands.

Over the years the lines between the two designations have merged, until it seems arbitrary as to why one guitar is called 000 while a similar guitar is called OM.

But, as usual for Martin history, the facts leading up to it all are not so simple.

For those who might need to know, the “scale” we are referring to is the length of the string from the saddle to the nut, i.e. the part of the string that is played and fretted to make music. The longer the scale, the more string tension and resulting resonant energy, but the wider the space between each fret on the neck.

It is worth pointing out that the string scales during the vintage Martin era were actually 2-7/8″ for the short scale and 25″ for the long scale. They were in place by the 1870s. But no one seems to know when these two measurements were adjusted to the 24.9 and 25.4 used today.

And it may be helpful to remind folks that acoustic guitar sizes tend to follow this system:

Concert (Martin size “0”)

Grand Concert (Martin size “00” – similar to Gibson size “L”)

Auditorium (Martin size 000 or size OM)

Grand Auditorium (Martin size 0000 aka size M)

Dreadnought (similar to Gibson’s round shoulder Jumbo size, and their square shoulder guitars like the Dove, and Hummingbird)

Small Jumbo (similar to Martin’s Grand Performance size and Taylor’s size 14)

Jumbo (similar to Gibson’s Super Jumbo)

Grand Jumbo, aka Grand J (similar to Guild’s Jumbo)

Read More at: Understand Martin Model Designations

This brief history lesson should help clear up some of the confusion surrounding the whole OM vs 000 conundrum.

1929

From the company’s founding in 1833 up to this point, Martin only made 12-fret guitars with sloped shoulders, similar in shape and look to modern Classical guitars, even though they typically had steel strings by this time. The largest size sold under the Martin brand was the 000. (The mammoth dreadnought size was made only for the Ditson music-oriented department stores, beginning in 1916.)

In late 1929, Martin made a special auditorium-size guitar with a longer neck, for popular band leader Perry Bechtel who wanted to transition from the banjo to the steel string guitar. Basically, they flattened down the shoulders on their standard body shape, which spread them wider while exposing two more frets for playing.

That guitar became the prototype of Martin’s revolutionary Orchestra Models, which were the first Martins designed from the ground up for steel strings, and which offered 14 frets clear from the body. In other words, they were the first modern acoustic guitars, with a direct influence on almost every flattop acoustic guitar that followed.

1930

Martin’s catalog offered for sale the new 14-fret guitars in their largest size, the 000, but the model stamp inside the guitar had the 000 replaced with “OM”, as in OM-18, OM-28, OM-45. The name Orchestra Model was a marketing ploy meant to attract banjoists in dance orchestras, who were converting to guitars, once they were featuring steel strings.

Most people do not know that Martin also offered the 1932 0-17 and 0-18 in the 14-fret orchestra model design as well, along with one special order 000-42. However, none of them got the OM as part of the model stamp.

But it is the actual OMs that matter here…

The OMs of that time went through a rapid evolution. For example, the small pickguard only lasted some six months (although some examples from 1931 exist.)

The bracing on the original OMs consisted of an X-brace that was 5/16″ in width, surrounded by smaller “tone bars” that were 1/4″ in width.

The straight bridge used for decades at Martin was replaced with a larger belly bridge, to better withstand the extra tension of steel strings.

1931

The Ditson department store closes during the Great Depression. Martin offers the Dreadnought body size under their own brand for the first time. The D-1 and D-2 are sold as test models and then quickly become the D-18 and D-28. Both have the 12-fret body design.

1934

Martin introduces a 14-fret version of ALL their sizes from 0 to the D. Any 14-fret Martin is considered to be an “orchestra model,” as opposed to the 12-fret “standard models.” For example, the 14-fret dreadnoughts appear in the 1934 catalog as “Orchestra Model, Size D.”

Martin changes the stamp inside the OMs to “000” so they may return to their normal size designations. Therefore, a 1933 OM is identical to a 14-fret 000 from early 1934. They are the exact same thing.

Sometime during the first six months of 1934, Martin changes the 14-fret 000s to the short scale already used for the 0 and 00 sizes, leaving the dreadnoughts as the only long-scale Martins. And the bracing on the 000 changes to 5/16″ for all braces, around the same time. Long-scale 000s from 1934 remain among the most desirable Martin guitars.

1939

Martin changes their neck width for all 14-fret models from 1-3/4″ at the nut to 1-11/16″, and changes the string spacing at the saddle accordingly, from 2-3/8″ or 2-5/16″ for most guitars to 2-1/8″ (equal to the fingerboard width of the 12th fret on the new more-slender fingerboard.)

1946

Martin changes all bracing to non-scalloped “straight” bracing. (Actually, this evolves starting in 1944.)

So, by this time, all 000-size Martins are short-scale guitars, with a 1-11/16″ neck and 5/16″ non-scalloped braces. This 14-fret 000 design remains in place for the next 60+ years.

1969

A guitar shop in Pittsburgh convinces Martin to make a small batch of “OMs” that have a long-scale 1-3/4″ necks. This was Music Emporium, which moved to Massachusetts in 1970.

1970s

By 1970 the only 000s remaining are the 000-18 and 000-28.

Various small-shop luthiers begin to offer guitars for fingerstyle guitarists that are closer to the old Martin OMs.

Martin remains conservative, offering OMs in small limited editions throughout the 1980s. They have 1/4″ scalloped bracing across the top, to better simulate the lighter, more responsive build of the 1930s Martins.

1990s

In 1990, Martin finally introduces the modern OM into their main catalog. The guitar has the same body size as the 000, but it has a long-scale, 1-3/4″ neck with compatible string spacing, rather than a short-scale, 1-11/16″ neck. OMs continue to have scalloped 1/4″ bracing, while 000s have straight 5/16″ bracing.

The OMs are also offered with the smaller “teardrop” pickguard similar to those seen on the earliest OMs from 1930.

By the end of 1994 the modern Standard series OM-28 and OM-45 have come and gone, but the OM-21 and eventually the OM-42 take their place. All were made from Indian rosewood and Sitka spruce.

In 1996 the OM-28V enters the new Vintage Series of Martin guitars. Also made from Indian rosewood and Sitka spruce, it offers more vintage-esque features than the Standard series OMs, like wider string spacing and a V neck shape. The mahogany OM-18V soon followed, as too did the Adirondack spruce-topped Golden Era Series OM-18, OM-28, and the OM-45, the latter two made with Brazilian rosewood.

As for 000s, the introduction of the Eric Clapton models in the early 1990s provide short-scale 000s that have 1-3/4″ V necks and scalloped 5/16″ braces. The 000-42 is eventually released in the Standard Series, even though it has the exact same construction as the 000-28EC in terms of scalloped bracing, neck shape, and string spacing.

Sometime around the turn of the century the first major blurring of the lines between OM and 000 appears, as Martin expands their more affordable series of guitars below Style 18, and the decision is made to offer all such 000s in the long scale, which has become the industry standard.

The OMs below Style 18 continue to have a wider neck and thinner braces, but scalloped braces and a long-scale neck have finally come to the contemporary 000s.

And yet, the Standard series 000-18 and 000-28 retain the short-scale neck and straight 5/16″ bracing.

Post-2000

All heck breaks loose.

OMs below Style 18 go extinct, leaving only long-scale 000s.

The Golden Era/Marquis series of Martin guitars introduces the 000-18GE and later the 000-42 Marquis. Both guitars offer 1/4″ scalloped OM-style braces on a short-scale 000, for increased response and resonance. This series also features Adirondack spruce tops and a more-vintage-like scalloping to the braces.

The John Mayer signature model offers an OM with a 1-11/16″ neck, and the lines between OM and 000 continue to blur further.

Please bear in mind there are exceptions to almost everything I have said so far, when it comes to limited editions, special editions, artist signature models, etc.

To make matters more confusing, Martin recently decided to put their new “High Performance Neck” on their Standard Series OM-28, OM-21 and 000-18, so they now have the same neck shape and string spacing: 1-3/4″ width at nut, 2-1/8″ at the 12th fret, and 2-5/32″ string spacing.

In practical terms, it has the dimensions of the previous 1-11/16″ neck, only cheated out a bit wider near the headstock, and with a tad wider string spacing at the saddle.

At least the 000-18 gets the scalloped 1/4″ braces it deserves, while remaining a short-scale guitar. And the OM-stamped guitars continue to have a long-scale neck and classic 1/4″ OM braces.

2016

Martin introduces the OMC-18E, OMC-28E, and OMC-35E to the Standard Series. Each is an Orchestra Model with a Cutaway body and on-board Electronics.

This re-introduces a long-scale OM in Standard Styles 28 and 35, and an OM with Standard Series specs in Style 18 for the first time ever.

All of these guitars have the modern High Performance Neck.

Only the Standard 000-28 remains as the lone 000 alive and kicking with straight, non-scalloped 5/16″ braces, and a short-scale, 1-11/16″ neck with the Low Profile neck shape.

The OM-42 remains as the only OM left standing with the low profile neck and a traditional fingerboard taper of 1-3/4″ at the nut and 2-1/4″ at the 12-fret, with 2-1/4″ string spacing.

Both models sell too well for Martin to change them, thus far.

2018

Martin introduces its “Reimagined” Standard Series, with all models getting the High Performance Neck and string spacing, plus new standardized cosmetic appointments for Style 28, among other changes. Read More at: Understand Martin Model Designations

The 000-28 FINALLY gets scalloped bracing. Interestingly enough, they get the 5/16″ scalloped bracing like the Eric Clapton models, while the 000-18 retains its 1/4″ scalloped bracing like an OM, with no explanation offered (to me from Martin) as to why this is.

There is also now an OM-18, well an OM-18E with electronic pickup system. But it is the first cataloged OM-18 without a cutaway offered by Martin in their Standard Series, ever. A purely acoustic OM-18 is likely to turn up sometime. But as stated above, the long-scale OM-18 and the short-scale 000-18 now have the same fingerboard width at nut, string spacing, and the same 1/4″ scalloped bracing, while the short-scale 000-28 and 000-42 have 5/16″ while their respective OM counterparts have 1/4″ bracing.

And when it comes to the 000s made below Style 18, the 16 Series and 15 Series 000s still get the long-scale neck and 5/16″ bracing. But the 17 Series 000s have a short-scale neck and 5/16″ bracing. And the Road Series 000s get a short-scale neck, but with a 5/16″ X brace and 1/4″ tone bars not unlike they very first 14-fret OMs that started it all in 1929.

All in all, it is easy to see how someone would look at the current Martin lineup and wonder; why would a long-scale Auditorium-size guitar made in the various series below Style 18 be called a 000 rather than an OM?

When it comes to Martin guitars, the answer is rarely as simple as the question.

2019

The Modern Deluxe Series debuts at Winter NAMM 2019, with two models that add to the tandem OM – 000 Design. They have the same bracing and each has the new Vintage Deluxe neck profile. Despite the various unusual construction features they retain the same sort of differences in tone and dynamics that show off the importance of the short scale vs. the long scale.

000-28 Modern Deluxe Review with Video

OM-28 Modern Deluxe Review with Video

Like this:

Like Loading...