Today is the 260th anniversary of the birth of poet Robert Burns.

While I have not attended a formal Burns Night Supper in years, I still celebrate in my own way, each and every year.

This evening, I am taken

back several years to the Immortal Memory given by my scholarly university mate, Thomas Keith, at a public Burns Supper given at the First Presbyterian Church on 5th Avenue, in Greenwich Village.

Today is the 206th anniversary of the birth of poet Robert Burns.

While I have not attended a formal Burns Night Supper in years, I still celebrate in my own way, each and every year.

This evening, I am taken back to the Immortal Memory given by my scholarly university mate, Thomas Keith, at a public Burns Supper given at the First Presbyterian Church on 5th Avenue, in Greenwich Village.

Therein, Thomas dispelled the stereotypical image of Burns as a hard drinking libertine (by those who associate him with the old Scots comic songs he collected and sometimes rewrote) by presenting detailed analysis of the poet’s working life and family life, and the sheer volume of his literary life.

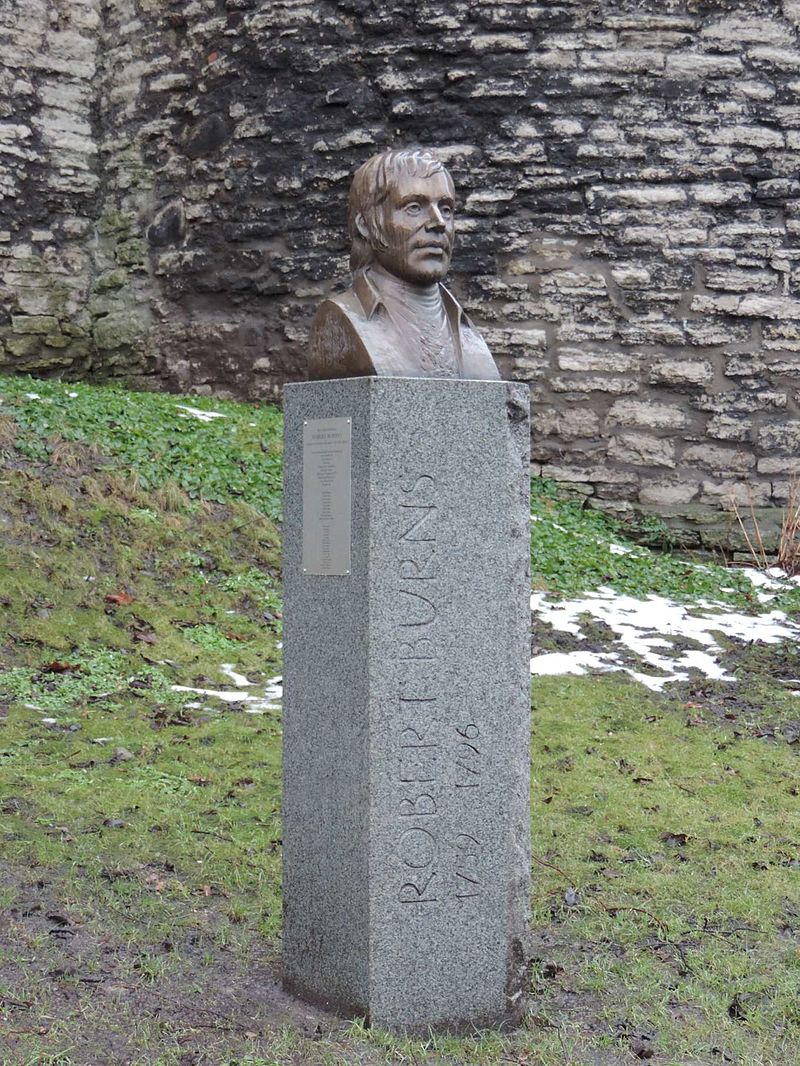

That is what people like Lincoln and Emerson found so inspiring. And that is why he remains revered wherever there have been popular revolts against oppressive rulers, from the former Soviet satellites to Latin America. And why there are more statues and memorials to Burns in the USA than anywhere else outside of Scotland; even then if only lesser by one.

He grew up when slavery was still legal in Scotland. And like Lincoln, he was mainly home-educated and worked at extremely hard agrarian labor from an early age. And both men could relate to the plight of those in bondage who were paid nothing, and those of the lowest freemen whose backbreaking life profited only their landlords, with little hope of improving the tenant farmer’s lot.

And at this troubling period in our own time, his observations on those on high whose character and true worth are in no way on par with their status can really hit home.

He is appreciated to this day for being ahead of his time when supporting both the American and French Revolutions, when that was a most unpopular position in the UK and the rest of Europe.

And here in this article, a Scotsman argues that Burns’ impact on American culture goes beyond the songs of Bob Dylan to having a direct hand in ending slavery here and in a deep influence on American poetry itself.

But that is not why we have Burns Night Suppers, really.

We do it because how how we relate so clearly to his love and celebration of life’s simple yet profound pleasures, often residing and reflected in “objects in nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom.”

That is what brings a tear to the eye, when one is surrounded by their boon companions, reflecting on the joy of the moment and the sheer profundity of our fleeting lives.

His sincere belief in the brotherhood of mankind is why we gather around the globe, in small cottages and extravagant halls, in every hemisphere and on every continent, on this night or whenever we can find the time go meet, and lament that “Young Rabbie” only lived to be 37 years of age, and why we celebrate the eighteenth-century Scotsman whom we like to believe would have liked us as much as we are sure we would have liked him, and who would have accepted our invitation to join us at our table, to raise a glass and sing a song, or seven.

To the immortal memory…

“Sláinte!”