Milton’s hand-annotated copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio found in Pennsylvania

Wishful thinking? Or the real deal?

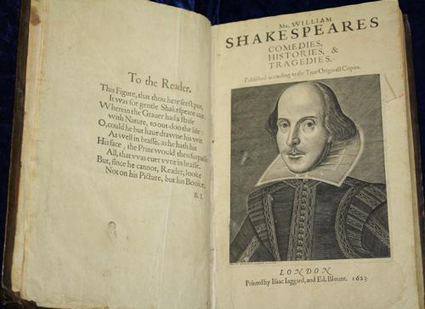

As announced on 9 September in the blog for the Centre for Material Texts at Cambridge (England,) it has been discovered that the First Folio of William Shakespeare’s works housed at the Free Library of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) may have once belonged to John Milton, the other immortal lion of English literature, who was 7 years of age when the Bard of Avon died. If confirmed it is one of the greatest discoveries of its kind.

A paradise of Shakespearean scholarship lost but now found?

This classic British detective story begins with an article written by an American college professor, Claire M. L. Bourne, of Penn State University, which appears in the 2019 volume, Early Modern English Marginalia. CMT Director Jason Scott-Warren was impressed with Bourne’s analysis of “highly unusual” annotations left by a writer of exceptional learning who was obviously familiar with Shakespeare’s literary sources, as well as versions of his plays published individually before and just after his death in 1606. The physical evidence suggests the handwritten notes were added between 1625 and 1660.

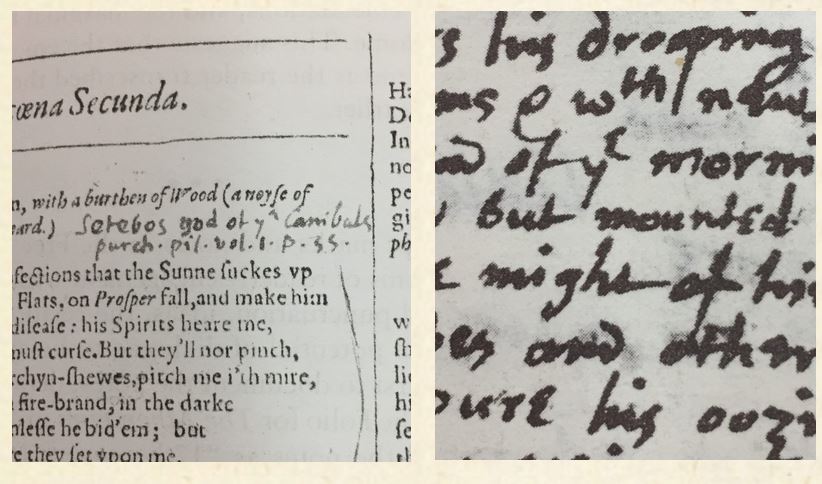

But the evidence that made Scott-Warren guess the hand was the same that wrote Paradise Lost was purely palaeographical – it looked like Milton’s handwriting.

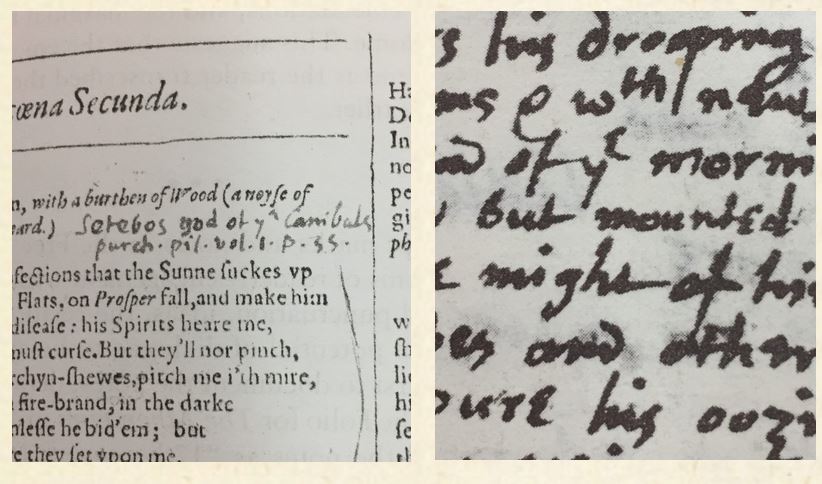

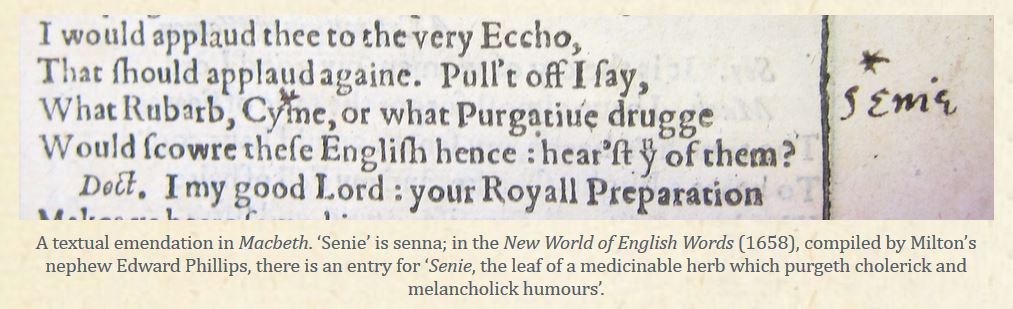

He goes on to provide photographic comparisons between writing in the Folio and writing in other books believed to have belonged to Milton.

Scott-Warren is quick to downplay his discovery as possible wishful thinking. But he adds postscripts saying he has received support by various scholars who are convinced he is correct. And he includes additional hi-res photography provided by Associate Professor Bourne in support of his hypothesis.

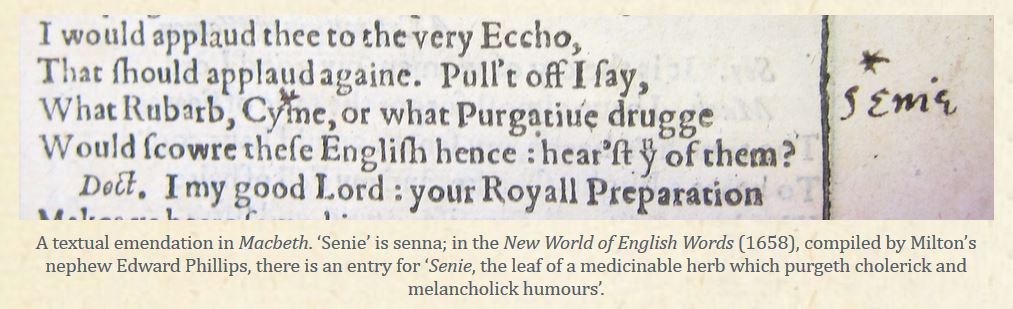

But I feel the contextual evidence is also compelling. Who other than Milton would have corrected the printer’s spelling of an obscure herb with the spelling found in Milton’s nephew’s book?

“If this book is what I think it is, it’s quite a big deal, …” Jason Scott-Warren allows himself to admit with typical English reserve, “… since Shakespeare was, as we know, a huge influence on Milton. The younger poet paid tribute to his forebear in an epitaph published in the Second Folio of 1632, in which he testified to the ‘wonder and astonishment’ that Shakespeare created in his readers.”

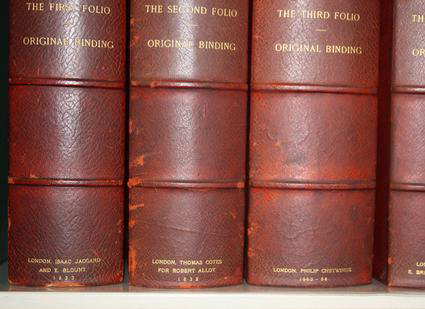

The Free Library of Philadelphia’s Book Department also owns copies of the Second, Third, and Fourth Folios, which were published in later years and include other plays attributed to Shakespeare, although all but one, Pericles, Prince of Tyre, have been disqualified by modern scholarship. The Second Folio even contains a poem now assigned to Milton. The Library’s folios are all in the original bindings and were donated in the 1940s by a philanthropic family who had made similar lavish donations to that same institution since the late 1800s.

Mankind was fortunate that Shakespeare’s fellow actors collected and published the plays of the First Folio seventeen years after his death, as eighteen of these important works might otherwise have been lost to history.

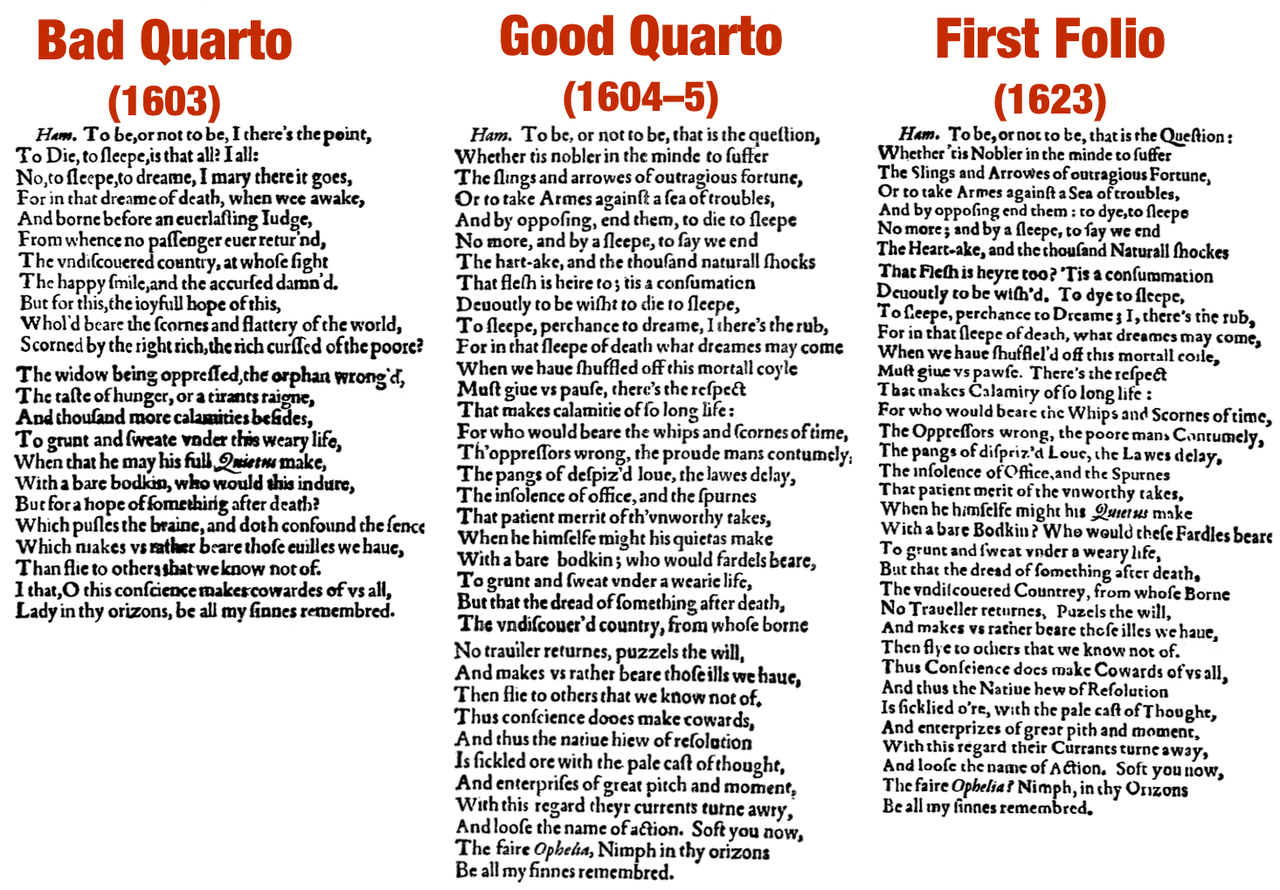

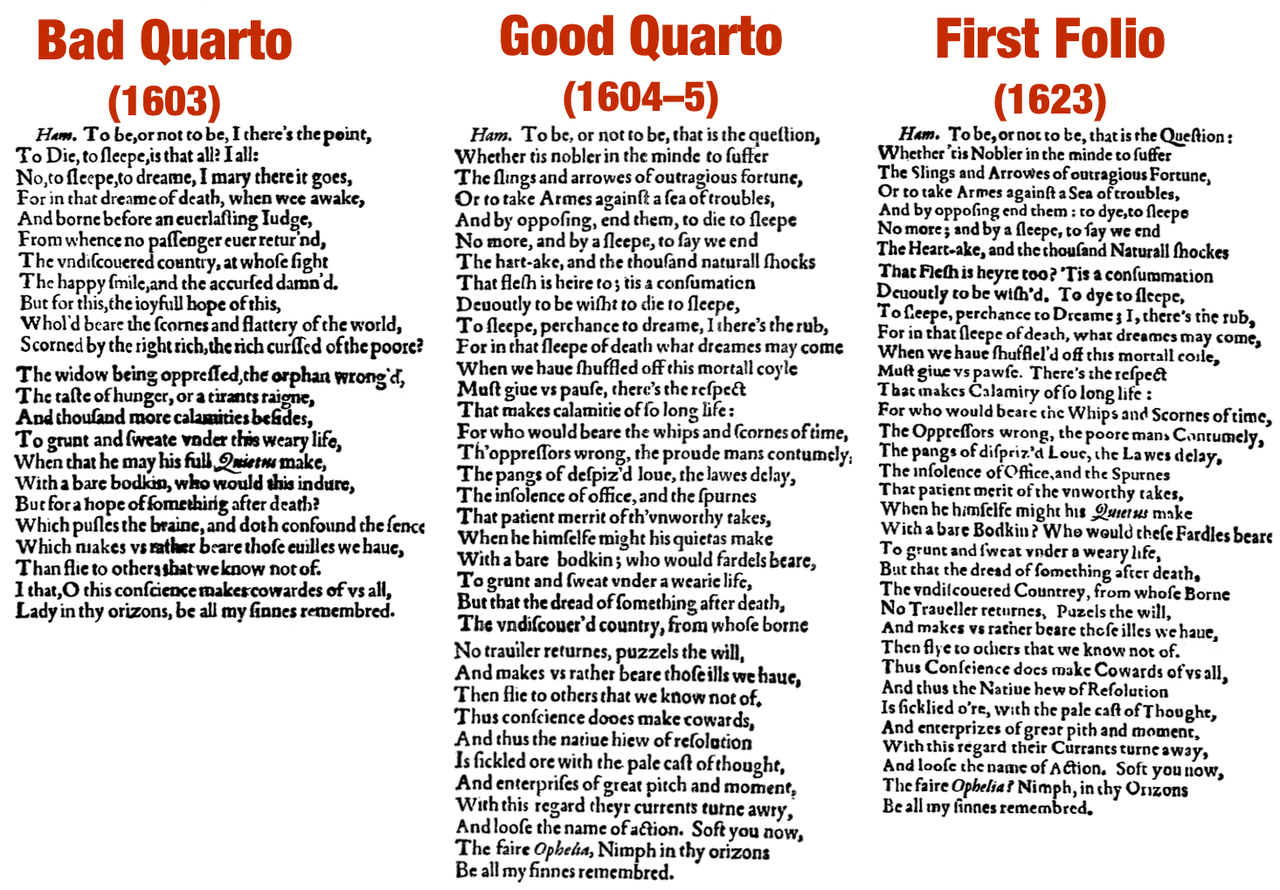

It is also interesting how many of these plays were published previously in smaller volumes, called quartos because the sheets of paper are printed with four pages on each side before being cut to fit into the binding. Some quartos are considered legitimate, and some are counterfeits put out at a time when the playwright’s work was considered exclusive property that one must pay to see performed.

photo: Wikipedia

And Milton, if he is the annotator in question, was familiar with some of these texts and includes references or entire passages not printed in the First Folio. Whoever they were, they knew their Shakespeare cold.

After the blog post appeared, many other scholars have come forward in support of this new discovery. From the Guardian:

“Not only does this hand look like Milton’s, but it behaves like Milton’s writing elsewhere does, doing exactly the things Milton does when he annotates books, and using exactly the same marks,” said Dr Will Poole at New College Oxford. “Shakespeare is our most famous writer, and the poet John Milton was his most famous younger contemporary. It was, until a few days ago, simply too much to hope that Milton’s own copy of Shakespeare might have survived — and yet the evidence here so far is persuasive. This may be one of the most important literary discoveries of modern times.”

And that is pretty darn cool.

Read Jason Scott-Warren’s revelatory blog post HERE

Suggested Reading:

Merlin Fragments Discovered – predate known English versions

Directors Discuss Tennessee Williams, America’s greatest playwright

Pinter’s No Man’s Land is still peopled by the good ghosts