Updated 11/11/19

While we dedicate this day to honor all veterans, the reason we do it on this specific day should never be taken for granted. The eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month was when the First World War came to its official close, back in 1918. Ninety-seven years ago today.

The end of a war should be commemorated, with giving thanks and celebration, both. Just as its beginning should never be forgotten, while we mourn all that was lost during the war.

Anyone who went to war will have their own personal sacrifice to live with, if they were fortunate enough to live through it in the first place. One does not have to serve in a front line unit to end up in harm’s way, but only the veterans who served in actual combat know the full measure of such service. And yet, we can all know that such events give good reason to mark the end of wars, lest we forget what happens in them.

That fact has never been more important than right now, as the United States has been at war longer than ever before in its history – even if most Americans hardly notice.

“On Armistice Day the philharmonic will play and the songs that they sing will be sad…”

The Great War of 1914-1918 remains unique in our collective history. Tactics developed during the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War met and were bested by modern weaponry capable of horrors never before visited upon mankind. The results exceed what civilized humans can imagine.

In one battle alone, on the River Somme, there were over one million casualties, with 310,486 killed outright and many more dying in the coming months as a result of their wounds. On a single day in 1916 the British army lost over 57,000 men in one engagement. Such numbers make the American losses on D-Day seem like footnotes. The losses of the French and Germans during the many battles around Verdun are beyond comprehension. And they kept at it; bravely charging into the of face death again and again.

On the whole, the world had never seen anything like it. Unfortunately we cannot say such things were never seen again.

Today the 11th November is referred to as Veterans Day and has been expanded to remember and honor all veterans who served their country ever since, in peacetime and in war. That is a good thing.

For some years, I would choose this day to open a cardboard box with some remnants of my grandfather’s time in the U.S. Navy.

There is a photo of a group of jovial sailors. The penciled script on the back says it is from 1912 and shows “a group of electricians on the Louisiana in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.” My grandfather sits smiling among them, and that implies he was involved in at least one of the two actions against rebels in Cuba that year. He later took part in the invasion of Mexico when they occupied Vera Cruz and tried to capture Poncho Villa. His unit went ashore to lay telephone wire in support of the Marines, and did some demolition work.

Then came the Great War. By the time he went overseas he had joined to the 1st Aeronautics Corps, where he operated an in-flight observation camera and machine gun. He qualified as an observer in St. Rafael, France, but spent most of his fighting time based in Italy, first at Lake Bolsena, north of Rome, and then at a base on the western coast at Corsini. From there they attacked the Austrian Empire across the Adriatic sea.

Their aircraft were the large Macchi M8 bomber, a flying boat that took off from the water with a two-man gondola, landing with the help of pontoons sticking down from the lower wing.

An Italian Macchi M5 fighter with US Navy colors circa 1918

An Italian Macchi M5 fighter with US Navy colors circa 1918

My childhood interest in my grandfather’s photos had to do with the planes and the war itself. I found it a thing of awe that they often were engaged in combat against the German Albatross D.III, the same lethal fighter plane piloted by the Red Baron when scoring 24 of his 80 aerial victories. Only in later years did I start to notice the people in the photographs and wonder who they were and what became of them.

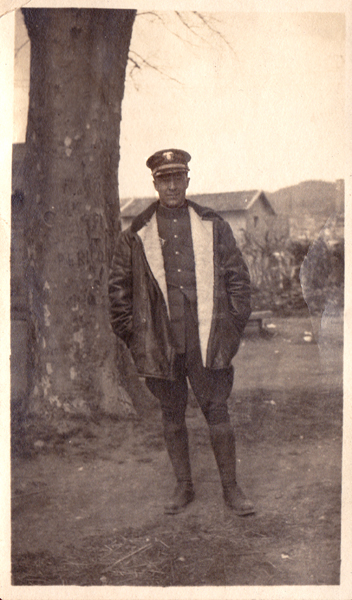

There was this particular man who really stood out to me. Man? Many of them seem boys to me, as I look at the photos from the perspective of advancing age. They were much older when seen in my childhood.

He always appeared well-groomed and serious, more mature than the rest. He just looked like a confident leader and someone other people admired.

I kept one photo of this man, because it was the only shot that displayed the officer’s uniform from head to toe. One can see the high boots with those odd bands of tight cloth that go around the leg just below the knee, which was the style of the time. He looks out from the photo with a subtle smile like he is happy someone is snapping his photo.

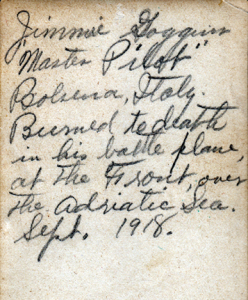

I had the photos for some years when I began to read the backs, which usually just mentioned where they were taken and sometimes who was in them. But on the back of the photo of the cool looking officer is written in my grandfather’s flowing script, in pencil with that fancy capital F that people no longer use these days,

“Jimmie Goggins, Master Pilot. Bolsena, Italy. Burned to death in his battle plane at the Front, over the Adriatic Sea, September 1918.”

And just like the first time I read that, anyone who has looked through that box has had the same reaction, as our fascination with adventures and daring do in canvas covered biplanes changes to a contemplation of the lives lost in wars and the sorrows visited upon countless families as a result.

In the same box is a larger piece of thick construction paper. On it is a hand-colored drawing, showing patriotic symbols like an eagle, the American flag and a G.I. fighting man of the WWII era. These would have been handed out or sold to servicemen to send home. On the back there is a short note, also written in pencil.

It says, “Mr. and Mrs. Murphy, From a foxhole in France I wish you a very merry Xmas. Love, Walter.”

My mother had no idea who this would have been. She was 15 in 1944. Our only fighting serviceman during that war from my mother’s side was her brother-in-law. By that Christmas he had been on many harrowing missions in action over North Africa and the Mediterranean. He was part of the first American unit to bomb Europe and took part in the Berlin Airlift after the war. Later, he commanded a squadron of KC-135 Stratotankers under the Strategic Air Command. His son fought with the 101st Airborne in the jungles of Viet Nam. In 2017 an extraordinary documentary was made about his rifle platoon, Phantom Force Revisited.

My father was 16 in 1944. His youngest uncle was in the Submarine Service in the Pacific and told REALLY frightful stories at his brother’s funeral. My dad’s own service included air patrols as a navigator and radio man over the Arctic Circle during the 1950s. His colorblindness kept him from being a pilot. That’s him in the backseat of this F-89D Scorpion.

He designed the blue fox insignia used by his squadron. After six years he was discharged and went to law school thanks to the GI Bill. Some years later his favorite pilot went missing in action over North Viet Nam.

Every time I go through this box I think about that. And I wonder what happened to Walter, and to all the Jimmies and Walters.

And it reminds me that November 11th is about much more than discussing who got the day off and which of us had to go to work. It is about other folks, past and present who had to go do a job very different from any I have done. In the UK they call it Remembrance Day.

I like that, as there is much to remember.

My grandfather’s leather flying helmet, goggles, scarf, and identity bracelet.