Crete and the Aegean During the Bronze Age – Monday Map

Its Crete to Me!

But is Cretan Grecian or the other way around?

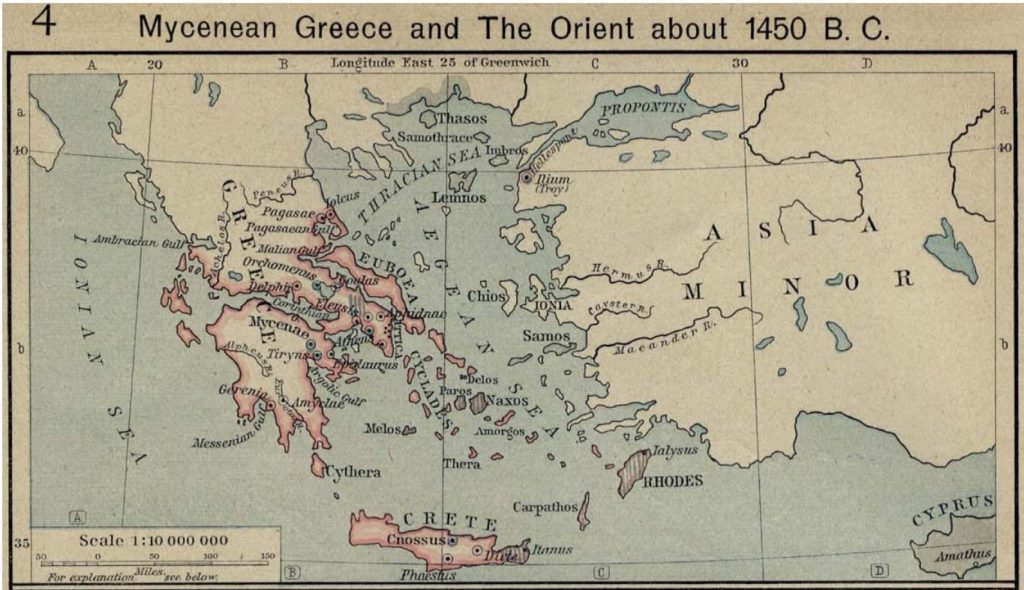

Credit: University of Texas at Austin. Historical Atlas by William Shepherd (1923-26)

The Newest Old

One thing the sciences have shown to be a certainty is that any prevailing theories will eventually be adjusted, perfected, or fall entirely as new evidence comes to light, or old data is interpreted through fresh points of view. This has likely been the case since the scientific method first arose in the third century BC, on and around the island of Samos, along the coast of modern Turkey, at the eastern edge of the Mediterranean, among what is now called the Ionian Colonies of Ancient Greece.

Although we tend to speak of such development in swathes of centuries, as one colossus of science or philosophy influences the next, in reality it is an ever-evolving enterprise forwarded by countless minds.

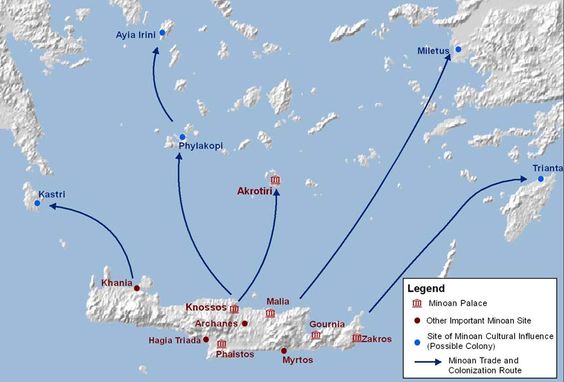

I was reminded of this fact when I read a commentary at Classical Inquiries of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, relating to the latest rethinking of the connections between two civilizations of the ancient world, the Mycenaeans of southern Greece and the mysterious Minoans of the island of Crete, who flourished more than a thousand years before the likes of Aristarchus and Epicurus were fomenting their intellectual revolution on Samos.

The earlier inhabitants of that isle would have almost certainly been on the trade routes of both locations, even if it was a long and convoluted trip for Bronze Age sailing ships, in the best of weather and wind.

Source: nonnotionuhiqa.blog.com

Having read some bits every now and again about who influenced whom and why the Minoans retired to oblivion until they were rediscovered in the early twentieth century, I found it tremendously fascinating to catch up on the latest interpretations. And you might too.

The author of this commentary is Andrew J. Koh, who I met and became friendly with when he was doing his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. After spending many seasons as an archeologist in Greece, he is now a member of the faculty at Brandeis University and M.I.T.

In barely more than a dozen years he has been in on many discoveries relating to life in the ancient Aegean, and the many more opinions and arguments regarding what they will ultimately teach us about the founders of our Western Civilization, and the daily lives of the common people who resided there, so many, many generations ago that it is stunning when I stop and try to fathom such an expanse of time and history.

There are plenty of links to related reading in the notes.