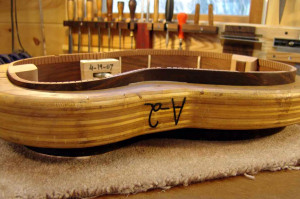

A review of a Brondel A-2 begins the new series on indie luthiers.

From a small workshop in the mountains of western Maine, Laurent Brondel applies technology and methods of progressive luthiery in combination with the hand-tooling and traditional craftsmanship of the master artisan, to create distinctive custom musical instruments.

Each Brondel guitar is one-of-a-kind, made one at a time. This specific example was completed on March 27, 2010, and represents a particular point in the evolution of the luthier’s very personal style of guitar making. Specs include:

A-2 body size, similar to a 14-fret orchestra model; hide glue construction; figured solid cocobolo back and sides; solid, domed Adirondack spruce top with unique amber burst shading; hand-carved, long-scale, one-piece solid mahogany neck, 1-3/4” width at the bone nut; ebony fingerboard with abalone dot markers; asymmetrical ebony bridge with 2-3/8 string spacing at the bone saddle; cocobolo headstock veneer; cocobolo binding; oil varnish finish.

“The voice is dominated by strong, solid fundamentals, clear and straight off the reflective top of Adirondack spruce, standing firm over a cocobolo sound box that imparts a fudgy rosewood richness, smooth and dense, but never so dark that it turns murky.”

Handmade the New Fashion Way

From the hand-carved neck to the inlays created in-house and protected under the glistening sheen of a hand-rubbed oil varnish, I love the special little touches on this guitar that make its one-off handmade persona known in subtle and tasteful ways.

The neck feels carved, not cut out of a mold. It is comfortably shallow near the nut, where the wrist bends at the most unnatural angles. It gets a bit thicker in the upper frets, more so than typical for such a low profile beginning, but nowhere near as massive as vintage-style necks.

This is not a table leg rounded on a lathe and buffed smooth by a robot. As I slide my hand up the neck where it begins to increase in mass around the 5th fret and beyond, there is a bit of an incline to the slope, and I can almost see the thin, curlings of mahogany being shaved away by a chisel or draw knife. And as the neck widens across my palm, the smooth surface retains a carved feeling, like it was sanded by hand with special attention given to locations where the luthier wanted it to be just right.

The purfling around the top consists of a band of dark wood with two thin lines of golden wood inside each edge. But the interior line is actually made up of many short segments that tilt inward with a bit of a curve near one end, overlapping the next segment. This gives a twisted rope appearance from afar. At other times there is an illusion of spinning motion as the eye follows the trim. The back strip and rosette have a similar motif. It seems a simple design, but the marquetry is exquisitely executed.

The entire aesthetic is downplayed in favor of the natural beauty of the wood. Even the abalone dots marking the fretboard start out rather small and decrease in size. The most flamboyant thing on the front is the headstock faceplate, made of figured cocobolo with nothing but tuning pegs to get in the way.

The one obvious indulgence is the shaded top, with a yellowish center spreading out into darkening hues of amber, similar to some early examples of shaded tops found on pre-war Martins. I have never been a fan of sunbursts, but this one is just so well done!

Photos do not do it justice. The center appears to glow with light rather than reflecting it. The blushing amber is never dark enough to obscure the grain in the spruce, which is crossed by lovely rays reminiscent of fiddleback maple. They hover long and straight under the glowing toner like thin wisps of mist at sunset.

|

|

|

First Impressions

On his website, Laurent Brondel says he aims to build “a guitar with a rich sound, yet with great clarity and projection, responding with a wide dynamic range and easy to play and hold.” That is a pretty good description of this one.

The tonewoods conspire and compliment each other very nicely. The voice is dominated by strong, solid fundamentals, clear and straight off the reflective top of Adirondack spruce, standing firm over a cocobolo sound box that imparts a fudgy rosewood richness, smooth and dense, but never so dark that it turns murky.

The unwound treble strings ring like bells that trill with a reflecting shimmer. But like the amber shading that never overwhelms the natural beauty of the wood, the Adirondack spruce keeps the lower registers from losing definition. It acts as a sharp focus lens, sculpting detail into the profound cocobolo warmth, like white caps on the crests of wider waves.

Colorful Cocobolo

The cocobolo on this guitar is a delight to hear and to see. It has a hue on the redder side of cinnabar, behind closely set staves of dark brown grain. The pattern on the bookmatched back, with its evenly spaced striping of varying thickness and darkness, looks like closely packed reeds, or layers of pleated drapery, slightly drawn apart down in the middle of the lower bout, with the folds in the fabric curving back toward the center as it nears the neck. Falling from each shoulder is a swag of decorative bunting, made up of wider concentric loops in the grain, slanting out toward the binding.

Matched to this back are reddish cocobolo sides of long, narrow, undulating bands with blackish borders, straight but wavering here and there in unison, before sloping up toward the spruce top as they come around the shoulders. The banding on each side aligns perfectly where the neck meets the body, so that it looks more like art than an accident of nature. And thanks to the cocobolo binding, it all seems to be an extension of the drapery covering the back.

|

|

|

Cocobolo is perhaps the densest of all the American rosewoods used in luthiery (African blackwood being the densest true rosewood.) Guitars made of cocobolo are often heavier than other guitars and require more powerful playing from a guitarist, even if a reward is found in serious volume and a powerhouse personality.

But this dense, oily tonewood can also be worked to greater thinness resulting in an instrument that responds well to subtle, nuanced playing while still putting out rich, colorful tone. And that is what happened in this case. While it was heavier than other Brondels played in the same session, it was lighter than many other cocobolo guitars. And it finds ample middle ground between responsiveness and power.

Inspired Interpretation

Brondel’s guitars are inspired by classic designs created at C. F. Martin & Co. during the early twentieth century, but with notable differences. With its long-scale neck and particular body size, the A-2 is most similar to the Martin OM, or orchestra model, from the early 1930s. And the bracing under the top is pretty much laid out in the exact same pattern seen on a pre-war OM, including the scalloping that shapes the tone bars to resemble the points and troughs of a suspension bridge. But he also included two extra scalloped tone bars just inside the sound hole, parallel to the strings. One end of these braces is mortised into the X brace and the other is mortised into the large traverse brace supporting the upper bout.

This A-2 represents a certain time and place in the evolution of Brondel guitars. In the years following the creation of this instrument, Brondel changed his bracing to be less traditional.

Learn more about this evolution at the luthier’s Q & A page HERE.

Laurent Brondel’s education as a luthier included a stint working for Pantheon Guitars with Dana Bourgeois, who is also known for instruments built in the Martin tradition with their own variations. After he left Pantheon to become an independent luthier, Brondel retained the modern neck configuration used on Bourgeois guitars and other brands like Huss and Dalton, which allows for an easily adjustable neck, both in terms of the truss rod accessible from the headstock, and a bolt-on neck joint. As string tension and the wear and tear of seasonal changes in humidity take their toll on the action, the neck can be adjusted potentially forever.

This guitar also features a top radius of 20 feet and a back radius of 15 feet, achieved by using a radiused dish while gluing in the braces. This results in a noticeable curve up and out from the sides compared to traditional flattop guitars like Martins, which have a 1.5 degree angle to the top, providing a radius somewhere between 45 and 55 feet.

Having a greater dome should allow a top that resists stress better than a flatter top, and remains stable with less bracing or at least less massive bracing. And while the domed radii of the top and back may have a lot to do with this guitar’s notable sensitivity, this certainly hasn’t taken anything away from its impressive bass response.

photos: L. Brondel photos: L. Brondel |

|

|

Getting Down Into the Sound

From the first arpeggio, the low E string makes itself noticed, standing out as the loudest string, instantly making this Brondel A-2 quite different from traditional OMs that have a dominant A string. And yet, the powerful low E is not disjointed and separate, but remains rooted down inside the voice, similar to the lowest string on a traditional dreadnought.

All the fundamentals are direct and distinct. Not only does a note form and peak immediately, like turning on a light, it remains firmly at that peak beyond the point where any reflection or harmonic arises, which are also quick to appear, almost simultaneous to the fundamental that sparked them, without intruding upon the integrity of the fundamentals.

This gives the impression of a stout note that forms quickly and remains in place in an elongated manner, with considerable unwavering sustain. This too is different from traditional OMs, which tend to have notes that bloom more slowly, as the undertone and upper sympathetics unfold and roll out like ripples on a pond, usually as the thinner fundamental note wavers and begins to recede.

Although these Cocobolo-rich notes are fat with warmth and presence, the immediate report and projection allows each fundamental to stand out clearly from the others when played in quick succession across an arpeggio or melody run. And even though successive notes stand apart and defined, the immediacy of both the played notes and their initial reflection make strummed chords arrive as a solid unified chorus with the lowest note and highest note standing out firmly and defined like trimmed edges.

The actual notes from the strings retain their initial peak for just a bit longer than what my ear is used to hearing from a guitar that appears to be made in the Martin vein. Seeing how this is a Brondel adaptation of a Bourgeois take on a Martin design, it is not really that surprising, as there are many un-Martin-like features at play, when one looks into the details.

Three-Dimensional Tone

There are other guitars of quality that offer steady fundamental sustain, all made with the modern neck joint and other departures from the traditional Martin paradigm, Bourgeois being just one good example. But none I am familiar with offer such an immediate fundamental note with such quick reflection accompanied by that elongated sustain. And I cannot remember playing a guitar where the low to high aural scale took on such palpable 3D presentation. It is like a swimming pool with a shallow end under the trebles of clear, sunlit water, which turns thicker like broth, as it drops off into a deep end lost to sight. Not that it has shallow trebles. Rather, the mids and lows just go so much deeper, and are so much thicker.

This sonic imagery comes from having unwound treble strings that take shape above the horizon, out in the air in front of the guitar’s top, with only their reflection reaching below the surface, like a strobe of fluttering sonar ricocheting inside the sound chamber. The report of the G string happens right at the surface, projecting equally out of the guitar and down into it, while the D, A, and E strings actually fire downward inside the sound chamber more than they jump out of it. They stand out into the room very well, but they reach farther into the inner space of the voice than do the high-mids and trebles.

While the low E string can sound even louder than the treble strings when it’s attacked, it is also the deepest string, reaching way down inside the voice, without sending too much of its deep dark influence sideways to muddy the space below the other strings – often a problem for rosewood guitars with scalloped braces that can create loads of erratic undertone.

Other than the unwound treble strings, there isn’t much of an undertone to speak of. Actually, the reflection from the lower notes is so quick to fire and so fast in its cycles, barely wavering off pitch before realigning, that it provides the sonic illusion of one fundamental note of fat presence and impressive sustain. Even if the lowest tones are so plush they can seem furry, each note from each string sounds colorful but clear, since they do not crash into each other’s airspace.

When a chord or series of notes are played on this Brondel A-2 and left to hang in the air – that they do. They stack like layers of clouds, hovering in place, or like the bands of a rainbow, where each may cross over to the next a little bit, but for the most part every color remains richly distinct from the others.

That sounds like I am describing the voice of a jazz archtop guitar, where each note in a Bbmaj13(#11) chord sounds isolated and true. This guitar actually has way more in terms of woody warmth and harmonic overtones. But the fat fundamentals and ringing sympathics are all well behaved and stay very much on pitch even as they fade, unless the player alters the string pressure or applies vibrato, when the notes respond instantly and mirror the physical sensation applied with the same sort of clarity.

So this guitar is extremely responsive, both in terms of how quickly physical energy is converted to audible sound, and in terms of dynamics and its ability to sense and react to subtle variations in attack and fretting technique.

For a rosewood guitar this is not particularly dark in terms of a loss of definition. The presence is more one of warmth and richness, and is nowhere as smoky and murky as, say, an Indian rosewood OM made at Santa Cruz or C.F. Martin. Although the player is enveloped by that warm voice, the clarity remains. The Adirondack spruce provides all the focus and refinement required.

And for an Adirondack guitar, there is plenty of that chrome plated chime glinting off the trebles with harmonic angels singing over top of them, but not much in the way of brittle dryness. Some of that is due to the cocobolo, but mostly, I think, the top has had some years to relax and loosen its prim Adirondack stays, as it were.

photos: L. Brondel photos: L. Brondel |

|

|

Finishing Touches that Add so Much

Any guitar made of cocobolo and Adirondack spruce will provide the tonal coloring of this tonewood combination. But that is only part of where a guitar’s voice comes from. Most of its personality is provided by the luthier.

Laurent Brondel has developed building techniques that are the synthesis of various influences, which he has combined and tweaked to his own satisfaction, and that of anyone lucky enough to own one of his creations.

In contrast to the way the top notes stand out, focused and precise to the ear, the white spruce back braces are veiled from the eye under a layer of cocobolo. Being dark brown, it keeps them from glowing like white stripes when viewed through the shadowy sound hole. Brondel said that he does this for extra strength, allowing for a thinner more responsive back, but also because its looks cool.

I concur. Even though Brondel typically caps his back braces and center strip with dark hardwood like cocobolo, the aesthetic works particularly well with the shaded top.

While coming from a Martin to Bourgeois progression, Brondel has also been inspired by other modern luthiers such as Englishman Stephan Sobell. This is obvious in the shape of the headstock, but also in the asymmetrical bridge similar to that seen on a Sobell, which decreases in thickness from bass strings to treble strings. It also widens out once past the saddle area, more so on the bass side.

It is beautifully carved and lovingly shaped, as each wing is tapered to considerable thinness. The added width helps anchor the bridge, while the thinness must allow the bridge to help transfer even the most delicate vibrations out across the spruce soundboard.

It is not only a bridge betwixt strings and top, but between the artisan’s hands and how well the finished instrument responds in the hands of a musician. And in the case of this Brondel A-2, that is basically effortless.

My playing isn’t known for its delicacy. I like to dig in and often allow my emotional inspiration to move through my arm and into the strings. But that doesn’t mean I cannot appreciate an instrument that springs awake when barely touched. However, I am more impressed by guitars that can do that and still take a heavy hand.

I thoroughly enjoyed seeing just how big and loud I could make this instrument when I got down and dirty with some blues in an open tuning until the strings were spanking against the frets, or when I experimented with a flat pick to see where the fundamental notes crossed over from big yet clear to growling and barking. It is likely this guitar has never undergone such attack and intensity.

While it didn’t particularly like being played so hard, this A-2 has an ample dynamic range. And really, one cannot have everything. This guitar is much more responsive to light and normal playing than something like a Guild that was built like a brick smokehouse.

I was very impressed with the voluminous sound radiating from this guitar. It is surprisingly loud when coaxed and caressed. The fingerpicking examples in the video are being played with considerable restraint compared to similar reviews, as I dialed into the resonant sweet spot on a guitar I was unfamiliar with.

But the true revelation regarding the guitar’s expressive responsiveness came when the owner cradled his A-2 into his arms, looking down upon its glowing top like he was grateful to have it back safe and sound.

Forming a chord with his left hand, he slowly and ever so lightly swept the meaty edge of his right thumb across the strings. Each note lit into existence, standing up with glimmering clarity and precise separation, framed by a soft radiation of bass, all set upon a platter of warm cocobolo, like six firm cherries in the center of a wide wooden bowl.

“I love this guitar.” he said, more to himself than to me.

And that was one man’s word on…

I own a Brondel A2 in mahogany and Adirondack, and there are two things that strike me about this guitar: crazy fundamental sustain, and a spooky responsiveness specifically with vibrato. Top tier building which I highly recommend. This review convinced me to buy my Brondel.

Well put! And well bought!! Congratulations.

And it is always nice to hear when I have helped someone find a guitar that satisfies musical desire, or a builder who makes just such a guitar. Thanks for sharing!