Theater Review

Resurrected with new life, the two-act drama of misaligned memory that is Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land provokes peals of spontaneous laughter, continually disrupting the unsettling tension that weighs upon the audience at the Cort Theatre, on 48th St. near Times Square.

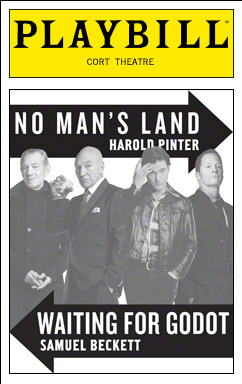

Starring Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart, and staged by director Sean Mathias, theirs is an affectionate production, bringing together two of the greatest speaking voices of our age to revel in the language finely formed by that most deft of English sculptors, the late Harold Pinter.

And yet, it is the characters’ spontaneous human behavior that tickles the audience, even as they are denied the sort of artificial exposition provided by other playwrights. In No Man’s Land are found no bread crumbs laid down to help explain what is going on.

Pinter’s insistence that the audience remain an outsider who becomes aware of lives and conversations well after they began, and which leave them long before reaching any definitive conclusion, is nowhere more obvious than in this play. With immediate prior circumstance barely mentioned, but memories from long ago recounted in vivid detail, he creates four souls who interact in anything but perfect harmony, and with two of the roles requiring champion actors to subtly conjure the weighty icebergs floating just below their visible surface.

The two knights of the English stage, McKellen and Stewart joust in Pinter’s No Man’s Land wonderfully.

The Plot Thinnens

Taking place during the 1970s, two men of a certain age enter an upper class sitting room in Greater London. The wealthy occupant appears to have brought home a rather seedy figure of questionable origin, the chance companions having met up in a public house near Hampstead Health, where they enjoyed “too many glasses of ale followed by the great malt which wounds.”

As inebriated as they are, it is soon apparent that the crumpled and unshaven Spooner comes from better breeding and higher education than his current state of dishevelment suggests. He seems to have fallen on hard times long ago, and he does what he can to ingratiate himself before his lofty host, a man of means named only in the program as Hirst.

The lead parts were written for no less than John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson, two immortals who famously rejected their intended characters in favor of the one meant for the other. With the supporting roles filled by Michael Kitchen and Terence Rigby, even the recording of the original production is an English language equivalent of listening to a string quartet performing a timeless piece of classical music. So much so, revivals have never quite done the work justice, until now.

Not much actually transpires in No Man’s Land, in terms of traditional action or plot development. Therefore, much depends upon the actors’ ability to flesh out the roles and bring their conversations off the page and into animated life. That is something this cast does very well indeed.

The greater portion of the first act is a showcase for the many talents of Ian McKellen, whose portrayal of the old down and outer is quite winning, thanks to the character’s self-deprecating humor and the veteran actor’s thread of vulnerability woven through his every reaction.

Stewart, as the well-off Hirst, is delegated the role of listener and occasional responder, presenting a bit of a dignified enigma who ultimately collapses from too much drink, and then crawls out of the room. But before Spooner can take his leave or take advantage of his singular surroundings, newcomers arrive.

The first to enter is Billy Crudup, as a rough edged Londoner named Foster. Crudup’s version falls short of the Pinteresque veiled menace that Michael Kitchen so embodied, but he brings to the role a charisma that makes him quite likeable and magnetic. It makes Foster’s confusion and suspicions regarding Spooner’s presence come off as more sincere and sympathetic than draconian.

Soon after, we meet Briggs, played with thuggish aplomb by Shuler Hensley. Clearly the brawn of the outfit, Briggs is older but less sophisticated than Foster. And when Hirst reappears, having awoken from a troubling dream, it is quickly apparent that these younger two are both the staff and jailors of their host, catering to his whims and thirst, but quick to prevent Spooner from making any inroads toward possible rehabilitation.

The second act takes place the next morning, with Spooner having been locked in the sitting room, only to be treated to a champagne breakfast and small talk provided by Briggs. Suddenly, Hirst appears well groomed and energetic. Although temporarily sober, he seems to mistake Spooner for a long lost college chum of a different name.

What follows is one of the great scenes in the Pinter canon, as two old men who were at Oxford during the same pre-war era meld their collective but faulty memories, of school days and war years, lovers and wives, promises and betrayals, with neither aware that they may have known some of the same people, but not each other. Or did they?

Long Shadows Cast by Giants

There is some irony in Ian McKellen’s performance. He has rejected any claim as the heir to the legacy of Sir John Gielgud, who first brought Spooner to life at the Old Vic in 1975. That regal knight with the Terry profile was famous for reciting Shakespeare without needing to lift a finger to support the lyrical utterance of what was once known as “THE voice.” Instead, the modern (yet also knighted) actor McKellen has always aligned himself with lineage founded in the more-natural, behavioral acting style associated with Laurence Olivier and Paul Scofield.

As much as McKellen may wish to be remembered for his naturalistic performances, he possesses one of those voices that could read from the phonebook and garner a standing ovation. He bestows such a rich and varied landscape across a string of spoken words that listeners quickly accept poetry rendered in his finely honed elocution as typical, everyday speech. More often than not, it comes off so naturally that the first person one speaks with after seeing a McKellen performance sounds like a donkey.

And the vistas of poetic imagery filling No Man’s Land are a feast for the ears, especially when so well rendered. In truth, McKellen’s love of the long vowel, setting up tension before releasing it with the short vowel pinched off by a sudden consonant, is no less an artist playing an instrument than Yo Yo Ma sawing away at his cello. But the actor anchors that vocal prowess in an emotional connection to his physical self, and to the point that voice and body become one (seemingly) natural being.

Even if he is repeating the processes 8 shows a week for many weeks on end, he mixes predetermined marks with absolute living moments and elevates the performance of everyone sharing his stage. And so, (sorry Richard Burton,) Ian McKellen has been placed in history as the uncontested heir to both Gielgud and Olivier, whether he likes it or not.

When it came to Patrick Stewart’s portrayal of Hirst, I was concerned at first. He seemed so frail and often impotent in his efforts to engage his livelier foil. Although the confusion and failings of memory he experienced as the character did embody the often frightening helplessness felt by those suffering from senility, which brought a new dimension to the role, Stewart seemed to lack the sheer power and presence that the late great Sir Ralph bought to every role he ever took on.

Thus I was wary of Stewart’s ability to fill such shoes. But my reservations proved misguided.

In Act II, Stewart’s Hirst enters as a new man, with a physical vitality and mental clarity that is as startling to the audience as it is to his companion of the night before. I immediately appreciated the deliberate sucker punch the actor (and director) dealt the audience. Where Richardson presented the same man drunk and sober, Stewart gave us an anemic and a revitalized man who was likely prone to such polarized states of being and seeing. In this latter part of Act I he is dressed in a robe of thin silk, revealing much of his aging body like a “figure reduced,” only to have him appear in Act II filling out a smartly tailored suit with perfectly groomed hair and the air of a man used to commanding his environs. (Stewart’s wig should earn the make-up artist an award.)

No slouch in the vocals department himself, Stewart’s command of the language throughout the second act, from his nostalgic recollections to his struggle to maintain a sense of control after repeated drams of whisky, brought to mind the decades he spent treading the boards of London’s West End and South Bank long before he became American television’s “sexiest man.”

Well into their seventies, these jousting knights are a good ten years older than the characters as written. But this helps them bring an egg shell delicacy to that sense of keeping their heads above water and their characters’ compelling desperation to preserve, or finally attain, some meaning in their dwindling days.

Gone But Not Entirely Forgotten

Frankly, witnessing two actors of their prowess playing off one another is like watching rock stars pointing their guitars at each other and letting fly, seemingly oblivious to the gathered fans straining to see over the hunched shoulders turned toward a respected rival. And Pinter’s particular alienation of the observer only amplifies the volume, so that we as an audience feel privileged to be there, laughing at inside jokes we only pretend to understand.

In time, we learn that Hirst is a famous poet, essayist and critic, “successful awfully early” but “past my best now.” Spooner never thrived, but may or may not host poetry readings at the same pub where Briggs saw him busing tables and cleaning toilets. And while Hirst seems to have it made and Spooner’s attempts to win a position in the household grow more desperate, both men have lost the families and friends that gave their lives any real meaning, back when each claimed a place “among the golden of my generation.” Gone are the summer cottages and lithe young women, and tea on the lawn. All that remain are ghosts of the nameless faces staring out from the photo album Hirst never gets around to finding. Hirst’s footmen keep him sedated with creature comforts, while Spooner over does every attempt to revive a dignity and promise long ago wrecked and left in shreds.

Ultimately we are confronted with the fact that imperfect memory shapes much of our personal perception of reality. In this production, there was a decided choice as to which facts were based in truth and which were not, and Spooner seems to be confused by his host’s delusions, humoring him until he too loses the thread of reality and points his own long-harbored resentments of an unfaithful wife in Hirst’s direction. A bit of a departure from Pinter’s intention, perhaps, but it worked well enough in the end.

Even if they sometimes go looking for emotional substance where the author suggested a void, rarely does one find such colorful artistry in the theatre as that presented by this seamless tandem of actors, fencing so well as they do live and on stage. At times it is like they are intoxicated by the poetic shoes they fill until they are glutted, in much the same way the alcoholic characters they portray suck down liquor and fine wine in staggering proportions.

If there is any major stumbling block to this production of Pinter’s No Man’s Land, it is found at the very end of the play. But that is the point seemingly unconsciously played out. Both Stewart and McKellen try to infuse profundity into their last lines, when it seems clear Harold Pinter expected Spooner and Hirst to chant their lines like out of some sort of tired ritual, before a congregation breaks up and life goes on. Instead, we have two actors near the end of their illustrious careers trying to milk every drop of meaning they can out of a juicy text, in their waning moments before an enraptured audience.

But as anyone can tell you who is old enough to know how much more revered and respected were the valiant crews of little torpedo boats, compared to the relative safety of destroyers, there is no ending to No Man’s Land, not while there remains breath in the combatants entrenched there. And as Stephen Brimson Lewis’ circular blue set and Peter Kaczorowski’s rounded lighting made clear, it has no edge or boundaries, and seemingly goes on forever, “icy and silent.”

As the house lights came on at the end of the evening, a woman in my row exclaimed, “I’m so confused!” That might have pleased the playwright whose peculiar arrangements of silence interrupted by the spoken word inspired the coining of the term “Pinteresque.”

And that is one man’s word on…

Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land, starring Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart

This production is playing in rep with Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, featuring the same four actors. The run has been extended through March 2, so I may get a chance to see Godot. I was fortunate in seeing the original McKellen and Stewart version twice in one week, at London’s Royal Haymarket Theatre, back in the Spring of 2009. Mathias’ production was a bit of a departure from Beckett’s bleak existentialist wilderness. Instead, it turned the two clowns and the passersby into literal ghosts of the Music Hall.

McKellen later toured the world with it. I should be very curious to see how much it has changed, with Stewart back in the role of Didi, and with Crudup and Hensley taking on the roles of Lucky and Pozzo.

Related Reading

More Culture Posts and Articles

~