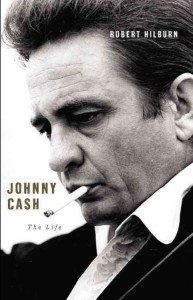

More than just another Johnny Cash biography, Robert Hilburn’s latest volume reexamines the rags to riches details of this unique example of the American Dream with its extreme peaks and pitfalls, as lived by one the nation’s most iconic musical artists.

The result is an insightful yet sympathetic analysis that conjures up the late Man in Black in living color, and argues that his was a life worth recounting, just as his art will be worth revisiting long after his era has passed.

The intimate portrait begins with the hard scrabble farm life of Cash’s early days in Arkansas, and recounts widely known incidences of his adolescence, army life, courtship and marriage, and early musical career. But the author’s portrait of the artist as a young man is steadfast in mining the formative experiences behind the mind, heart and soul responsible for artistic expression that was both uncommonly popular and profound.

The intimate portrait begins with the hard scrabble farm life of Cash’s early days in Arkansas, and recounts widely known incidences of his adolescence, army life, courtship and marriage, and early musical career. But the author’s portrait of the artist as a young man is steadfast in mining the formative experiences behind the mind, heart and soul responsible for artistic expression that was both uncommonly popular and profound.

These milestones include the childhood death of a beloved brother, the apple of the family’s eye, which left the young “J.R.” in permanent mourning and the need to gain the approval of a father who forever felt the lesser son had survived. The depth of his Christian faith and a love of gospel music instilled by his mother also date from the same period, and remained a pillar he often leaned upon when he had fallen into the worst parts of a self-titled sinner’s life.

Just as the young Cash broke into the professional music world, he discovered and become addicted to the amphetamines that would cause him and all those around him to suffer so much throughout his ascendency toward international stardom. Peddled by the government to front line troops during the Second World War, “pep pills” had become a national scourge by the time they became more tightly controlled in the early 1960s. Cash was only one among countless performers who used pills or other drugs to maintain their grueling schedules and often fragile egos, and he nearly added his name to the list of those who crashed and burned at an early age. Few outside his most intimate circle were aware of just how close he came to complete and fatal disaster.

Even though the Johnny Cash of the 1960s comes off as a reckless and often selfish personality with little regard for those he hurts along the way, the author also exhibits Cash’ self-awareness of his own failings, which allowed the music star to ultimately have compelling empathy for people of all types, and an acceptance of their imperfections.

His own uneven life experience provided sources of inspiration he tapped into again and again when he wrote songs about prisoners, and those average folk who were unlucky in life and love. And after he survived the worst of times, he never lost touch with his faith, his roots, or his sense of his own deficiencies. He came to identify with all sorts of underdogs and those hard pressed by unsympathetic powers greater than themselves, and, as one Columbia records marketing writer put, his music “speaks to the prisoner in us all.”

Hilburn draws on many published sources to flesh out the icon into an extraordinary and extraordinarily imperfect man. These include multiple biographies and the two autobiographies published during Cash’s lifetime, as well as interviews in the press from across his long career. While it remains unclear just how familiar Cash was with Hilburn, the author’s perspective of Johnny Cash was certainly a privileged one.

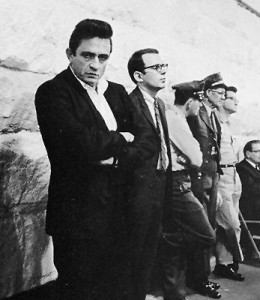

Robert Hilburn was a Cash fan since the singer’s days at Sun Records in the 1950s. He was working as a freelance writer for the Los Angeles Times in 1968, when he was the lone journalist to accompany Cash as he gave his legendary concert at Folsom prison. A year later he was on the full-time staff at the same paper, where he remained as the chief music critic and pop music editor until 2005. While he covered many of the era’s biggest stars, his interest in Johnny Cash never dimmed. It is clear this work is a labor of love, at times to the point of listing the many foibles and excesses while downplaying them at the same time.

For example, mention is made of the sexual exploits within the touring music star lifestyle, but never in the same detail provided about other similar persons, such as who was having an affair with whom, or the recounting of groupies lined up outside the dressing room of Elvis Presley, patiently waiting their turn to sacrifice some virtue to the latest pop idol. While affairs or infidelities that led to changes in Cash’s life are mentioned, at times it seems as if Hilburn seeks to exonerate Cash the man through worse examples quoted by intimate insiders. But he also uses quotes to better effect when describing the undeniable talent and artistry that made Johnny Cash matter so much to so many.

While he makes a point to credit each and every source, it is Hilburn’s ability to include the many quoted snap-shots within the smooth emulsion of his own smart prose that keeps the focus on events as they happen, present and alive. It is his insistence on allowing others to speak with emotion and opinion, while he sticks to the facts and resists grand conclusions, that provides a sense of authenticity to the story, and keeps the pages turning.

We hear from and about many of the personalities that helped define the era, like Bob Dylan and Kris Kristofferson, Merle Haggard and the Statler Brothers. But more often than not, Hilman’s own contributions to the tale are some of the best, even as he includes them in a humble fly on the wall sort of way, as in his recounting of the Folsom prison concert, or with a passing “he told me,” like the time Cash shared with him the memory of the banner years of 1969-1970, when he was invited by Richard Nixon to perform at the White House.

“I was at such a high point in my career and there was so much to be thankful for – (his new son and his wife) John Carter, June, the way God was coming back into my life.” He told me. “I had been on television hundreds of times, but the White House was something different. I was thinking. ‘If I die tomorrow, I want this show to demine my goal as a songwriter and entertainer.’”

Hilburn points out that the singer never voted, and would have been just as happy to have been invited by a Democrat. Even though he displeased some on the left who saw Nixon as the enemy, he refused to see anyone as wholly bad or entirely good, giving most everyone the benefit of the doubt. He was able to understand that America was made up of all of its people who had ever lived there, even if they didn’t all agree or deserve the same reverence, but that American institutions like the Presidency deserved respect as much as hard working railroad men, or the legends of the Old West.

And while the previous section, dedicated to the years of constant touring, does turn depressing with the details of excessive drug use and the collapse of his first marriage, it keeps the reader locked into the present moment so one is almost surprised that Cash actually survives to reach superstardom with a popular TV show, and a new family with June Carter, a member of Country Music’s most royal family.

Although his second wife is sometimes portrayed as a home wrecker and opportunist, those who know better will credit June Carter with saving Cash’s life and helping him through the hard fought bouts of rehab. When June appears on the scene, Hilburn dedicates an entire chapter to the Carter family, when he might have been able to sum up their importance in music history with a few sentences. He is writing with an affinity for his subject as well as a desire to make clear that Cash was as keen to be associated with the legendary Carters as June may have been keen to land a rising star of her own. But as their marriage continues until her death shortly before his own, they were clearly made for each other and the long haul.

Many people will come to this book remembering Johnny Cash as the grizzled old country music legend, who wrote some chestnuts about prisons and heartache, and who the Hollywood movie showed to be a bit of a likeable if bratty prima donna. Robert Hilburn reminds us exactly why Cash made such a big splash when he was launched by Sun Records alongside Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and eventually Jerry Lee Lewis, and why so many people put up with his destructive and often selfish personality during his meteoric years. He was a good man at heart, who remained rooted to his humble origins and who truly felt he could change people’s lives for the better through his music.

The author does a good job of chronicling Cash’s development into a true artist who balanced pop music recordings with deeper, more meaningful work, and who also grew and changed for the better right along with the work that reflected the broader society evolving around him, and which allowed him to reach audiences way beyond the core fans of Country Music.

The same year that Woodstock was rocking in the rain, Johnny Cash sold over 6 million records, more than any artist in history at the time, and he brought in a larger box office during his sell-out show at New York’s Madison Square Garden than that garnered there by the Rolling Stones or Janis Joplin. Hillman continually keeps things in perspective when it comes to the entertainer’s popularity, at a time when Country Music and Pop were considered water and oil, and in terms of how the universal appeal of Cash’s music transcended genre, regions, and generations like few performers before or since.

Although his television variety show was eventually cancelled and he was dropped by Columbia records, Johnny Cash never lost faith in his artistic vision, even if he thought others had. And at the end of his life he found a whole new way to express it, thanks to producer Rick Rubin, whose scaled-down and acoustic guitar-oriented American Recordings, “not only made Cash relevant again, but also cemented his musical legacy.”

And just as Hurt, and other songs and videos from the Rubin recordings introduced the MTV generation to the power and persuasion of Cash’s plain spoken tales of lonesomeness and redemption, Robert Hilburn’s biography of Johnny Cash provides a sort of greatest hits, taken from all the bios that will likely go unread by most book buyers today, while providing gems of unique insight and new revelations about an American original as imperfect and extraordinary as the land itself.

And that is one man’s word on…

Robert Hilman’s Johnny Cash: The Life

Published by Little, Brown and Company

A treasure to own. Just purchased the hard cover today. Thank you so much for your review. A D-35 will be next

Might have to read this!